In which Phillip Simpson (author of Minotaur, Argos, Titan).talks about the process of writing classical fantasy.

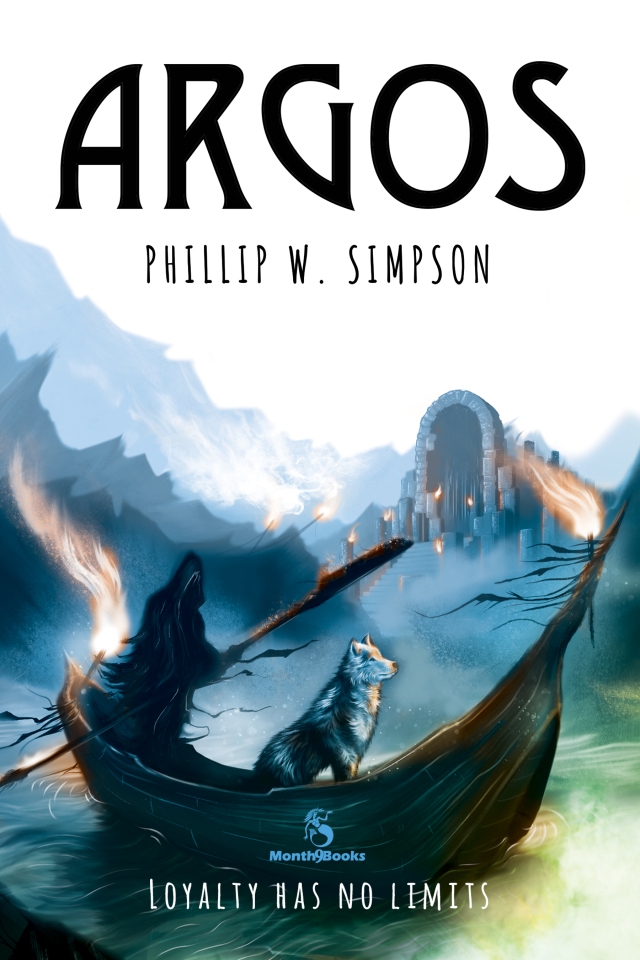

Phillip Simpson is a New Zealand fantasy novelist who is taking on the classical myths to interesting effect (Minotaur, Argos, Titan). I read and enjoyed Argos, the story of Odysseus’s faithful hound, and I asked Phillip if he’d be willing to be interviewed about the process of writing Classical fantasy. He was, and the discussion covered a wide range, from the changing nature of monsters, to the use of evidence in retelling classical stories. Read on!

What drew you to writing/working with Classical Antiquity and what challenges did you face in selecting, representing, or adapting particular myths or stories?

I grew up reading myth and legend, particularly classical. In fact I was obsessed with these stories. As an adult and a novelist, I came to the conclusion that all myth and legends are asking for a retelling. Why? Because no-one was around to verify the ‘so called facts’. Even Homer writing about the Trojan war in the Iliad wasn’t there. The Trojan war was around 1300 BCE (before Christian Era – essentially the same as B.C) and Homer was probably writing around 850 BCE. We are talking at least four hundred years difference here.

Stories from two years ago get diluted, exaggerated and wilfully changed. Heck, stories from two days ago get the same treatment. Do you expect any less from stories that are thousands of years old! So what is a myth and how is it different than fiction? Myths are verbal traditions. Why? Because most of the ancients were illiterate. The ancient Greeks certainly were (prior to and during the Trojan war). Seems odd to say it because the Iliad and the Odyssey are two of the more famous works of literature. Most of the ancient Greeks were duller than mud (in the literate sense). Sounds harsh but there you are. Not much smarter than your average preschooler. I wouldn’t say that to their face obviously because I’d be in a bit of trouble (if the events in the Iliad are anything to go by).

- Argos, the story of Odysseus’s wonderful dog

A myth is handed down generation from generation, story teller to story teller. They are part cautionary tale, part entertainment. They usually have a lesson to impart or a warning – essentially that if you mess with the Gods, you’re going to get it. If you are guilty of hubris (pride), then you’ll get it even harder. And don’t annoy Zeus.

Myths and fiction are old friends. You could say that myths were the first forms of fiction. The first best sellers, the first blockbusters. I’d imagine that great storytellers would’ve been regarded as rock stars with legions of adoring fans. That’s one of the reasons why I was drawn to the subject matter – the other is that I could take creative license. I take myths and fictionalise them. This fictionalisation was easily done due to a lack of eye witness accounts, scanty evidence and a tale that’s been twisted to promote the interests of whoever was the most powerful city state at the time (usually Athens). In other words, creative license. The two words an author loves the most!

In terms of challenges, my agent often chastised me for following the story arc too closely. I have too much respect for the myths to change them completely (or their structure) but she often had to remind me that I was writing fiction.

Why do you think classical / ancient myths, history, and literature continue to resonate with young audiences?

Mostly because they have heroes and monsters. And they will never go out of fashion. Humans have always been obsessed with stories containing these two and the monsters are always the draw card. Monsters have been around since the dawn of time, maybe in the very real sense but always haunting the darkest recesses of our overactive imaginations. The monsters were waiting for us as we swung down from the trees and started walking upright. They were there when we discovered fire and the use of tools and primitive weapons. Hey, they were probably the reason we discovered fire and invented weapons in the first place. As Shepard writes:

Our fear of monsters in the night probably has its origins far back in the evolution of our primate ancestors, whose tribes were pruned by horrors whose shadows continue to elicit our monkey screams in dark theaters (1996, p. 29).

Like many young people, I’ve always been fascinated by monsters, an interest and love nurtured by countless books on myth and legend. Many mythical monsters were based on eye-witness accounts. Early explorers came back from their adventures with tales of strange creatures. With no-one to argue against them, many were taken at face value. The unicorn myth, for example, was started by a traveler returning with stories of the rhinoceros. Some were based on fossil evidence. Ancient miners discovered dinosaur bones, lending credence to the dragon myth.

Mythical creatures were almost always made up of two or more separate animals. If they weren’t, chances are they would be half animal, half man. This is because scholars at the time used the world around them to describe and invent the more fantastical elements. For example, the chimera was part lion, part goat and part snake. The Minotaur was half man, half bull while the centaur was half horse, half man.

Almost all mythical creatures were based on an animal or animals that exist today. Writers used none of this creative business of making up a completely different and foreign (well, to us) creature that bore no similarity whatsoever to anything else.

But, as the centuries marched on, so too did its monsters, transforming with the times. Monsters emerged with more human characteristics—both physically and mentally. In Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein, the creation of Victor Frankenstein has both human appearance (although hideous) and easily recognizable human emotions, seen in his desire for acceptance, companionship and love. Bram Stoker’s Dracula was also recognizably human, albeit with supernaturally creepy abilities. Such as drinking blood for instance. Not that that’s an ability—more like a trait—but you get the idea.

Do you have a background in classical education (Latin or Greek at school or classes at the University?) What sources are you using? Scholarly work? Wikipedia? Are there any books that made an impact on you in this respect?

I do. My undergrad degree was in Classics and Archaeology. I studied predominantly Greek and Roman history (with some Near Eastern through in for good measure). Inspired, I then went on to do a Masters (Hons) in Archaeology and whilst I have a decent amount of experience in archaeological digs and a true interest in Maori pre-history, I always wanted to be involved in Classical archaeology. I went on to do a post-grad diploma in Museum studies and then moved to London.

- Minotaur (which Phillip dedicated to his classics teachers)

I even dedicated one of my novels (Minotaur) to my classics Professor, my archaeology Professor, and my classics and history high school teacher.

In terms of sources, when I was studying twenty years ago, the research process was very different. Everything I learned was from books—either my own or from the University library. These days, I do most of my research on-line. I am also guilty of what is referred to in teaching circles as ‘last minute learning.’ In other words, if I’m trying to find out what types of fruit they would have sold in a Greek market place in Athens two thousand years ago, I can just look it up. I can find what I need in a matter of minutes as opposed to spending hours poring through books. Research is a lot easier than it used to be. That said, I’m a big fan of Homer and Thucydides.

How do you think working from New Zealand and the Pacific affects your approach to classical material? Did you think about how Classical Antiquity would translate for young readers, esp. in New Zealand?

I don’t think my geographic location affected my approach at all. These are classic stories after all and the themes and popularity are universal. I did consider writing a novel based on Maori myth (and still am) which would obviously be more New Zealand specific and many New Zealanders would be able to relate (or be familiar with the source material). To be honest, I didn’t even think that classical antiquity would be a problem to young readers in New Zealand. That said, I have had some feedback regarding some of my books that they are harder for young people to relate to because they are set in the ancient past. The Percy Jackson series, for example, have modernised the myths and set them in present times. This has made them more relatable, something my agent often reminds me of.

How concerned were you with ‘accuracy’ or ‘fidelity’ to the original? (another way of saying that might be—that I think writers are often more ‘faithful’ to originals in adapting its spirit rather than being tied down at the level of detail—is this something you thought about?)

I definitely put a fictional spin on my retellings. In all fairness, however, the original stories were also a work of fiction (in all likeliness – you never know). I took what I knew, held it up to the light, turned it this way and that. Scratched some parts, polished others.

I always look at the archaeological evidence (old habits die hard). It helped that I was once an archaeologist. I pored over maps, especially ancient ones, read up on flora and fauna and worked out geographic routes. In other words, if I had to get from this point to this point and I was on foot, what would it look like? How long would it take? What would I eat? Etc. etc.

In terms of these myths, we know what ‘really happened’ but when all is said and done, to really know what happened is an impossibility. Writing didn’t exist then. It was a story based on an oral tradition. Nothing was written down. There are no photos. In other words, the only evidence exists from the story telling – the story has been told and retold over countless generations. Essentially, I have created my own ‘truths’ in my books.

When I’m reading about ancient history or myths or even about latest archaeological finds, I’m always thinking: ‘would that make a good story? Could I put a spin on that? Is that what really happened?’ It’s the last bit that particularly intrigues me. There is always an element of guesswork in archaeology. We can make informed guesses based on evidence but there will always be some doubt. Why? Because we weren’t there and what evidence we have is thousands of years old. In mythology, there is often not even that which gives you a great deal of room to reinterpret.

So, I’ll find a mythological or ancient historical figure whose story interests me. I’ll dig a bit deeper and see what other fascinating tidbits I can unearth. Then, the real work begins. I’ll use what is ‘commonly accepted’ as the truth (based on evidence or oral history) as a guideline. I usually try to stick to the original story but fill in all the gaps and speculation using creative license. At the back of my mind, I’m always thinking about how this story could’ve been diluted and modified over time. Is there another interpretation? Were the supposed ‘eye witnesses’ reliable? If not, why? What was their motivation?

Are you planning any further forays into classical material?

- Phillip’s latest foray into classical fantasy: Titan

I am. I have. My latest book, Titan, is out now and it’s a retelling of Zeus’ childhood and how he came to be King of the gods. Here’s the blurb:

Zeus, Father of Gods and men, god of sky and thunder, the Cloud-gatherer, wielder of the mighty thunderbolt.

But once, long ago, Zeus was none of those things. He was a young man, blissfully ignorant of his destiny, content to walk the shores of Crete by day and sleep in a cave at night, watched over by his foster mother, the nymph, Almathea.

Aided by his cousins, the Titan Prometheus and beautiful Metis, Zeus learns that he is a wanted man and that his brothers and sisters are held captive. His father, the dread Titan King Cronus, wants him dead. Zeus has no choice but to end his isolation and embark on a quest to free his family before Cronus finds him.

Their journey will take them to the starlit heavens, the crushing depths of the oceans and to the darkest, bleakest pit of Tartarus itself.

There, Zeus will seek to fulfil a prophecy and commit an act condemned by both gods and men for all eternity:

To destroy his own father.

–Phillip Simpson, in conversation with Elizabeth Hale

Interesting and lively!

Thanks.

LikeLike

Very intersting interview! I have to buy some of the books.

The interview reminded me on Isaac Asimov who once wrote a short story inspired by the Minotauros. In the story, the Minotauros was a friendly alien creature who visited ancient Greece. (I guess the humans didn’t get his good intentions.) Unfortunately, nobody wanted to publish this story, probably because Asimov tried to imitate Homeric language what might have been too much for the average reader. Unfortunately, the story is lost now.

LikeLike